My last stop in Malawi, the Mwabvi Wildlife Reserve, established in 1953 and expanded in 1975, and covering an area of 52 square miles, is Malawi’s smallest national Park or Reserve, and its least visited – it turns out for good reason.

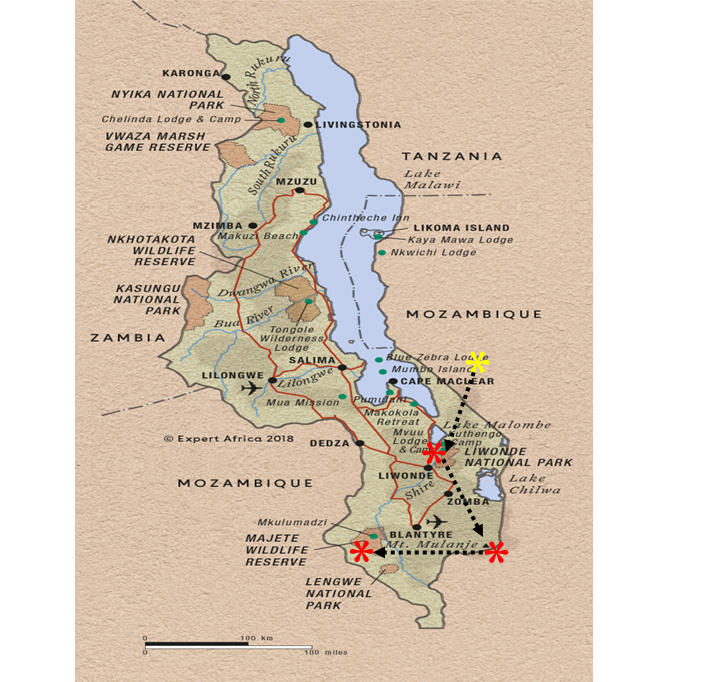

Mwabvi is located at the southern tip of Malawi bordering Mozambique. Like most of the other Parks and Reserves in Malawi, this one too is managed through a cooperative arrangement between the Malawian government and a private nonprofit trust called Project African Wilderness (PAW), which was formed to protect and restore the Mwabvi Wildlife Reserve. I suspect that Mwabvi was established originally because it was the last natural home to the black rhino in Malawi. However, as with the rest of the country, both wildlife and woodland have been heavily poached over the years, and thus there are few animals left today. Black rhino were hunted out many years ago and there has been no effort to reintroduce them given the management status of the Reserve (see below). As far as I can tell, and what little information I could glean from the Reserve entrance gate ranger (the only Reserve staff person I saw), there are only a few species of antelope left, such as kudu and duiker, but I saw none during my brief stay.

The reserve is situated in the Shire River valley, but it does not abut or straddle the River like Liwonde and Majete, so there is no riverside floodplain or riparian habitat. Instead, Mwabvi straddles a seasonal tributary (now dry). They claim that this Reserve has a wide variety of habitats, but all I could see was unbroken woodlands and the dry riverbed. Perhaps the most notable feature of the landscape is the occasional sandstone outcroppings that provide some relief. Here are a few photos of the relatively uninteresting landscape:

The story of Mwabvi is a sad one. Unlike African Parks, which manages Liwonde and Majete and has done an amazing job of recovering the wildlife populations and improving the infrastructure and facilities, PAW, as far as I can tell, has done absolutely nothing to protect and restore this Reserve. There is no obvious investment in infrastructure or facilities and, so far as I can tell, they have done nothing to protect and recover the wildlife populations. Consequently, there is almost no wildlife to speak of, and as a result, no one visits this Reserve. It appears as though the Reserve is simply a common area for the locals to rummage wood, grass and poach the occasional antelope for meat. It’s a shame, because given the location in the Shire River valley and the woodland habitat, this Reserve could be as successful as Majete with the right investment and management. Fortunately, I only had to pay $13 USD for the one-night stand.

I camped at the public campsite (Migudu) in the Reserve. This was the one redeeming feature of the Reserve. There are just 5 sites, but each are private and nestled up against some minor sandstone outcrops with both shade trees and – surprisingly – a water tap at each site. Amazing! There is no toilet, which is shocking, and it looks as if no one, including the Reserve staff (if there is any) has visited the campground for some time. Nevertheless, the campsite suited me just fine for my brief stay. Moreover, there were two very short trails leaving from the campground, one to a viewpoint and one to the dry riverbed. Note, I had planned on staying 3 nights in the Reserve, thinking there would be more to see, but after arriving and doing a little reconnaissance, I decided to bail after the first night and give myself more time elsewhere. Here’s my campsite:

I took a short video of my campsite and one from the viewpoint to share for those followers that just see my videos and don’t actually read the blog. Here it is:

Mwabvi Wildlife Reserve video (3 minutes)

Ok, I am off to Mozambique. See you there.