Time again to reflect on the country from behind the wheel. Note, these are not always observations from literally behind the wheel, but rather observations based on ponderings while driving – so, indirectly from behind the wheel.

In contrast to Zambia and, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe, Tanzania seems like a more progressive country focused on growth and development – not that that is necessarily always a good thing, as the human propensity to always develop, develop, devolp is in fact the primary cause of so many of our global crises. Nevertheless, Tanzania seems to be working hard to improve the standard of living of their people. Here are some specific observations, not all of which are positive and some of which are common to other southern African countries. In addition, many of the previous comments I have made about other countries also apply to Tanzania, but I won’t repeat them here, so the comments below are largely ones that I haven’t commented on yet.

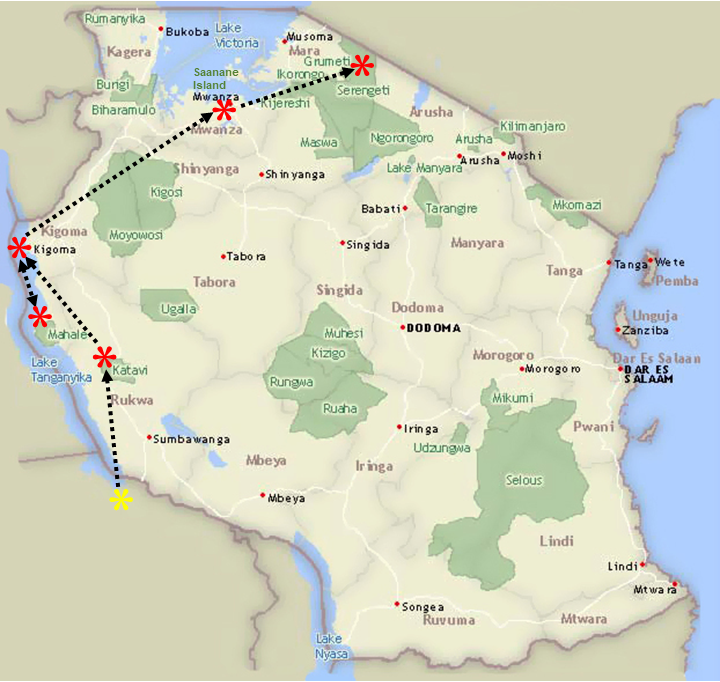

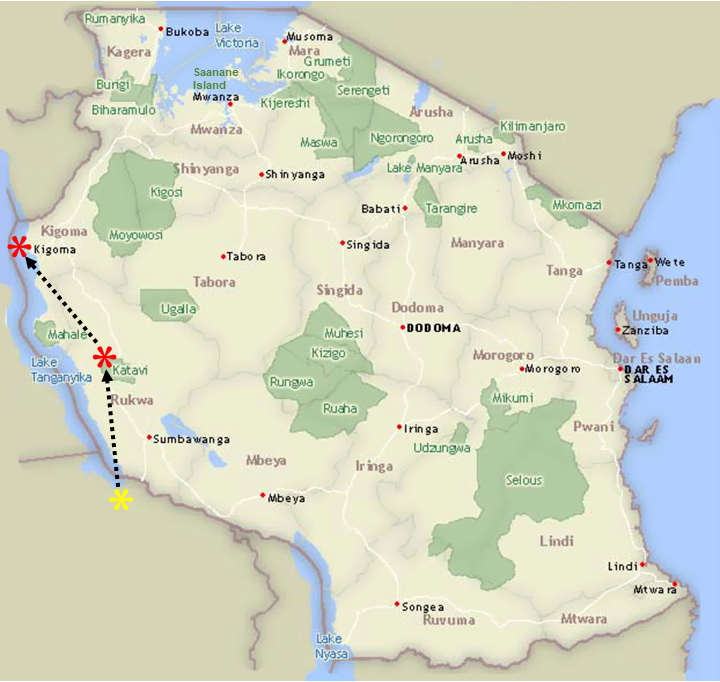

#1. Build, Baby, Build. The Tanzanian national highway system and even some of the major secondary roads are tarmaked and essentially pothole-free! Can you believe it? Even South Africa, a much more developed country, has far worse roads. I don’t believe I hit or even had to swerve past a single pothole while driving the highways of Tanzania. Moreover, the few sections of the highways system that are not tarmaked are under construction right now, including massive bridges over waterways. I am not sure how all this new highway construction is being funded, but one section had a sign saying “funded by the people of America”. I heard others say China and still others just said “the government”. In any event, when the rest of the highways are finished in the next couple of years, it will make getting from one part of the country to another (and from Park to Park) very easy. All I know is that my life would have been much more difficult if I had to drive all those miles on potholed highways or on gravel. Thank you Tanzania!

#2. Country Life. Here are some typical scenes traveling the roads of western Tanzania. Note the following. First, the entire area outside of established National Parks and Game Reserves is settled and developed, predominantly with rural small-scale mixed agriculture, but with some larger settlements mixed in. Lots of charcoal and thatch production, along with maize predominantly and a smattering of other crops such as sugar cane and bananas depending on the location – your basic subsistance land use with a little extra to sell to improve ones standard of living. Second, deforestation is a serious problem. Outside of the Parks and Reserves the forests are heavily cut over for fuel and building materials. Many of the tree species coppice or resprout, but they are cut again as soon as they reach any size. This land use activity, which is understandable given the living conditions, leaves the Parks and Reserves as “islands” for the remaining wildlife. Here’s a few photos of some typical scenes along the roads.

#3. Love Those Babies. Africa has the fastest growing human population in the world and is expected to contribute more to the global human population growth over the next half century than all the other continents combined. My observations of the population demographics would seem to support this claim. It seems like the youth make up the largest segment of the population followed by the child-bearing aged 20- and 30-year olds. Moreover, it is hard to find a young women – and too young at that – NOT carrying a baby on her back. I’m sure that 9 out of 10 young women in their child-bearing age were carrying babies on their backs as they went about their work. Indeed, I was surprised when I saw a young worman without a baby on her back or at her side. Given the poor economic state of at least the rural western part of the country, it makes me wonder how they are going to fare in the future. I am concerned about the welfare of this next generation of Africans.

#4. The Better Half. One of the things that is hard NOT to notice is that the women are almost always engaged in some kind of activity, whether it be getting water from the local bore hole, carrying produce on the head to market, hauling wood from the woodlands, tending the crops, washing clothes and a dozen other essential activities. In contrast, while there are cleary some ambitious, hard-working young men, a large portion of the young men in their teens and 20’s seem to be idle most of the time. It is common to see anywhere from a few to a dozen young men just sitting around doing nothing while the women all around them are working. It is as if the young men, after finishing secondary school, if they don’t find a real job they just sit around doing nothing while they wait for the gold to drop from the sky. It definitely seems to be a cultural norm that the men try to find work, but often fail, while the women take care of the children, household and farm, if they have one. And if the young men don’t find gainful employment, they don’t “lower” themselves to helping with the “women’s work”. I hate to say it, but a lot of the young men are not worthy of the family they have.

#5. Burn, Baby, Burn. Tanzania tops the list when it comes to the use of fire. While I have commented previously about the use of fire both inside and outstide of the Parks and Reserves to manage vegetation, Tanzania takes it to the next level. I estimate that 80-90% of the lands I passed through had been burned, or were still burning, this year. This 1-2 year fire return interval rivals that of the aboriginals in northern Australia. One of the many reasons they burn every acre they can each year is to produce a flush of nutritious new growth as seen in these photos:

#6. Karibu. I will end this on a high note. Karibu is a swahili word with multiple meanings, but is commonly used to say “welcome” when you are greeted, especially by service providers. Most Tanzanians appear to be genuinely pleased to welcome you to their country, and most are very proud and happy to be Tanzanians and share their country with you. Of course, some of this is business-motivated, but I get the distinct impression that most Tanzanians are truly happy to see you visiting their beloved country. It is the same welcoming atmoshpere that is prevalent in Botswana, but here it struck me as hallmark of the country, or rather the people.

There’s so much more that could be said, but I’ll save it for later. Cheers.